OK, let’s drop autonomous vehicles for a second. Things are getting serious. This post is about creating a machine that writes its own code. More or less.

Introducing GlaDoS Skynet Spynet.

More specifically, we are going to train a character level Long Short Term Memory neural network to write code itself by feeding it Python source code. The training will run on a GPU instance on EC2, using Theano and Lasagne. If some of the words here sound obscure to you, I will do my best to explain what is happening.

This experiment is greatly inspired by this awesome blog post that I highly recommend reading.

I am by no means an expert on deep learning, and this is my first time fooling around with Theano and GPU computing. I hope this post will show how easy it is to get started.

Some background

Neural networks are a family of machine learning algorithms that process the inputs by running them through layers of artificial neurons to generate some output. Training happens by comparing the expected output to what the network delivers, and changing the weights between neurons to try making them as close as possible. The math involves a lot of big matrix multiplications, and GPUs are really good at doing those quickly, which is why the recent advances in GPU computing made deep learning so popular and so much more efficient.

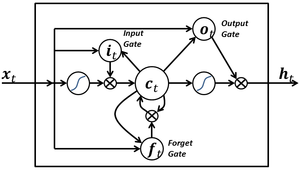

A lot of research goes into designing network architectures that are easy to train and that are efficient on certain types of tasks. Feed-forward architectures like convolutional nets are very good to deal with image recognition for instance. Here, we are going to talk about recurrent neural networks, which are good at processing sequences. One of the most popular architectures of RNN is Long Short Term Memory (LSTM) <– read this post if you want to know what is happening and why it is so good at dealing with long sequences.

We are going to use LSTM on sequences of characters. What happens is that we feed the network sequences of characters, and the network has to guess what the next character shall be. For instance, if the input is “chocol”, we expect the character “a” to follow. What is remarkable about LSTM is that they can learn long term dependencies. For instance, it can learn that it has to close parenthesis if it has seen the character “(“, and will do so even if the opening parenthesis was seen a thousand characters earlier.

As I said earlier, GPUs are much quicker to train such neural networks. The most popular framework for GPU computing is CUDA, provided by Nvidia. Most Deep Learning libraries have some interface to CUDA and allow you to perform computations of a GPU. As I write in Python, the most natural choice for me was Theano, a very efficient library for tensor calculations. On top of Theano sits Lasagne, a Python library that makes it easier to define layers of neurons, and has a very simple API to set up a LSTM network.

Step 1: Firing up a GPU instance

We are going to launch a g2.2xlarge instance and install everything we need in order to run our code. Most of the instructions are foundable here, so I am not going to rewrite them. I also installed Lasagne, IPython and Jupyter to write my code via Notebooks. The resulting AMI (with the rest of the code included) is available on the N. California zone on AWS with this id: ami-64f6b104. For more information on how to set up an AWS account and launch an AMI, you can refer to Amazon’s documentation directly.

We are going to use a Jupyter Notebook to write our code. I created a bash script that allows to configure the Notebook server, in order to serve it to your laptop. You will be able to write code directly in your browser and have it run on your instance. I basically followed these instructions. Be sure to rewrite line 24 of the script to set your own password.

Step 2: Gathering some training data

Ok, so we want to train a neural net to write some Python code. The first step for us is to try to find as much Python code available as possible. Fortunately there are a lot of open-source projects in Python.

I concatenated the .py files that do not contain test in their name for the following libraries: Pandas, Numpy, Scipy, Django, Scikit-Learn, PyBrain, Lasagne, Rasterio. This gives us a single file that weights about 27 MB. That is a reasonable amount of training data, but more would definitely be better.

Step 3: Writing code and enjoying :)

We can now write our code to train a LSTM network on Python code. This will be wildly inspired from this Lasagne receipe. In fact there is very little to change apart from the training data.

The network takes a few hours to train. We will be saving the network weights with cPickle.

After that, we can enjoy the first few lines of code that our little Spynet outputs:

I think Spynet is tired already:

assert os = self.retire()

It defines __init__ functions and adds comments:

def __init__(self, other):

# Compute the minimum the solve to the matrix explicite dimensions should be a copy of the functions in self.shape[0] != None

if isspmatrix(other):

return result

It learned to - approximately - use Numpy…

if not system is None:

if res == 1:

return filter(a, axis, - 1, z) / (w[0])

if a = np.asarray(num + 1) * t)

# Conditions and the filter objects for more initial for all of the filter to be in the output.

… And to define almost correct arrays (with one little syntax error). Note the correct indentation for line continuation:

array([[0, 1, 2, 2],

[70, 0, 2, 3, 4], [0], [3, 3],

[10, 32, 35, 24, 32, 40, 19],

[002, 10, 13, 12, 1],

[0, 1, 1],

[25, 12, 51, 42, 15, 22, 55, 59, 37, 20, 44, 24, 52, 34, 26, 25, 17, 32, 13, 43, 22, 44, 43, 34, 82, 06],

[0.42, 3.61., 7.78, 0.957, 1.649, 2.672, 6.00126248, 1.079333574], 0.2016347110, 0.13763432],

[0, 4, 9],

[13, 12, 32, 42, 42, 20, 34, 20, 12, 24, 30, 20, 10, 32, 45],

[0, 0, 0],

[20, 42, 75, 35]])

Ok, we may be far from a self-coding computer, but this is not bad for a network that had to learn everything from reading example code. Especially considering that it is only trying to guess what is coming next character by character. The indentation is often correct, and it remembers to close parenthesis and brackets.

However it mixes docstring text and code, and I did not find any function that would actually compile in the output. I am sure that training a bigger network as the one in this article would improve things. Additionally, loss was still going down when I stopped training so there was still room for improvement in the output if I waited a bit more.

The complete script used for training can be found here. Feel free to use the AMI and improve things!